Zarathustra’s discourse in this chapter addresses his “brothers”, and focuses on the nature of the state, which he metaphorically describes as the “new idol” and the “coldest of all cold monsters”. He personifies the state as a deceitful entity that proclaims, “I, the state, am the people”, a statement he denounces as a lie.

State is the name of the coldest of all cold monsters. Cold, too, it lies; and this lie crawls from its mouth: ‘I, the state, am the people.

Zarathustra emphasizes that each people has its own understanding of good and evil, developed through customs and laws, which their neighbors do not comprehend. The state, however, speaks falsely in all tongues of good and evil, stealing what it possesses. Zarathustra accuses the state of embodying falsehood in every aspect, with even its entrails being deceitful.

He observes that the state was invented for the “superfluous”, those who are overly abundant and unnecessary. The state entices these individuals, consuming and regurgitating them. It proclaims itself as the greatest entity on earth, the “ordering finger of God”, and seeks to surround itself with heroes and honorable men to bask in the glow of their virtues.

Throughout the chapter, Zarathustra denounces the masses drawn to the state—the “superfluous” who are constantly ill, seeking power and wealth without capability, and who devour each other without satisfaction. He compares them to hasty monkeys climbing over one another, dragging themselves into the mud in pursuit of the throne, mistakenly believing that happiness resides there.

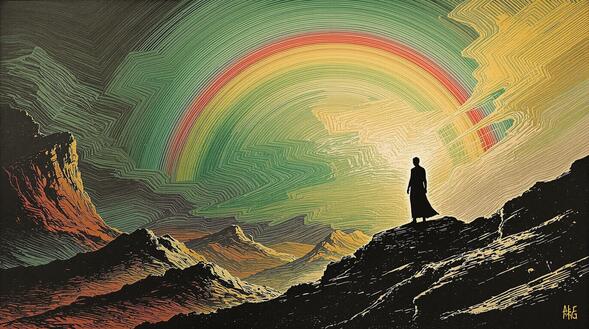

There, where the state ceases – look there, my brothers! Do you not see it, the rainbow and the bridges of the Übermensch?

He urges his brothers to avoid the foul stench of the state’s idolatry and the sacrificial offerings of these superfluous ones. Zarathustra calls for his brothers to break free, to seek spaces open to great souls where the scent of quiet seas prevails. He extols the virtues of poverty and freedom from possessions, suggesting that only where the state ends does the true human being—who is not superfluous—begin.