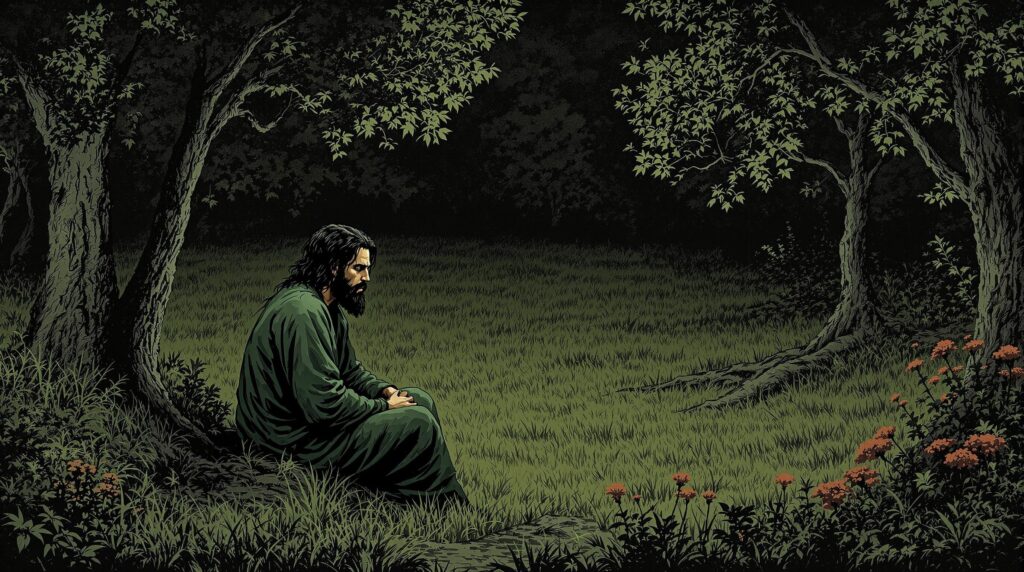

This chapter begins with Zarathustra walking through a forest one evening with his disciples. While searching for a spring, he arrives at a tranquil, grassy meadow encircled by trees and bushes. There, he observes young maidens dancing together. Upon recognizing Zarathustra, the maidens cease their dance, but he approaches them with a friendly gesture, encouraging them to continue. He assures them he is not a spoilsport or an adversary of girls, declaring himself to be an advocate of God against the Devil, whom he identifies as the “Spirit of Heaviness”. This spirit represents the burdens and seriousness that weigh down humanity, contrasting with the lightness and joy embodied by the dancing maidens.

Do not stop dancing, sweet maidens! No spoilsport has come to you with an evil eye, no enemy of maidens. I am God’s advocate before the devil: but he is the spirit of heaviness. How could I, you light-footed ones, be an enemy to divine dances?

Zarathustra describes himself metaphorically as a forest and a night of dark trees. He suggests that those unafraid of his darkness will find “rose-covered slopes beneath his cypresses”, implying deeper beauty and enlightenment beneath the surface. He references a “little god” dear to the maidens, lying quietly with closed eyes beside the spring—an apparent allusion to Cupid, the Roman god of love. Playfully, he considers chastising this “day-thief” who has fallen asleep in broad daylight, perhaps from chasing too many butterflies. Anticipating that Cupid will cry and laugh when disciplined, Zarathustra proposes to sing a song for his dance with the maidens—a dance and mockery against the Spirit of Heaviness, his most powerful devil whom some call the lord of the world.

As the narrative progresses, Zarathustra sings of a recent encounter with Life, personified as a woman. Gazing into her eye, he felt himself sinking into the unfathomable depths. However, Life pulled him out with a golden fishing rod, laughing mockingly when he called her unfathomable. She retorts that all fish say such things—that what they cannot fathom, they deem unfathomable. Life describes herself as changeable, wild, and entirely womanly, not bound by virtue, even if men label her “the deep”, “the faithful, “the eternal”, or “the mysterious”. She mocks that men project their own virtues onto women, highlighting the misconceptions and idealizations that cloud genuine understanding.

Despite her incredulity, Zarathustra admits he never believes Life when she speaks ill of herself. In a private conversation with his wild Wisdom, also personified as a woman, Wisdom accuses him of praising Life only because he desires and loves her. He nearly responds harshly, recognizing that telling one’s wisdom “the truth” is the most severe retort. He reflects on the complex relationship among himself, Life, and Wisdom. Fundamentally, he loves only Life, especially when he harbors animosity toward it. His affection for Wisdom arises because she reminds him intensely of Life; she shares Life’s eyes, laughter, and even her golden fishing rod. He muses on the uncanny similarity between the two, pondering the elusive nature of both.

When Life once inquired about Wisdom, Zarathustra eagerly described her allure and elusiveness. He speaks of an insatiable thirst for her, looking through veils and grasping at nets. Uncertain of her beauty, he notes that even the oldest carp are still lured by her. Wisdom is changeable and defiant; he has observed her biting her lip and combing her hair against the grain. Perhaps she is wicked and deceitful, thoroughly womanly; yet, paradoxically, when she speaks ill of herself, she becomes most seductive. Upon hearing this, Life laughs maliciously and questions whether he is speaking of her, challenging whether such truths should be stated so plainly. She urges him to speak similarly of his Wisdom. Zarathustra laments that when Life reopens her eyes, he feels himself sinking again into the unfathomable depths.

The sun has long since set, he said finally; the meadow is damp, and a coolness comes from the woods.

Something unknown is around me, and is looking thoughtfully.

After the dance concludes and the maidens depart, Zarathustra is enveloped in melancholy. He observes that the sun has long set, the meadow is damp, and a chill emanates from the surrounding forests. An unknown presence seems to contemplate him. In this introspective moment, he questions his continued existence: “You still live, Zarathustra? Why? For what purpose? By what means? Where to? Where? How? Is it not folly to still live?” He attributes these probing questions to the influence of the evening, asking his friends to forgive his sadness, acknowledging that it is the evening that presses such contemplations upon him.