In this chapter, Zarathustra delivers a profound discourse on the nature of life, power, and value creation. The narrative unfolds as Zarathustra addresses the “wisest” individuals, challenging their pursuit of truth and their understanding of existence.

He begins by critiquing the so-called “Will to Truth” that motivates the wisest. He asserts that what they truly desire is to render all existence thinkable and to impose their own will upon it, bending reality to fit their intellectual frameworks. This desire to make everything subservient to the mind he identifies as a manifestation of the “Will to Power”. Even when these sages speak of good and evil and assign values, they are expressing a will to create a world that aligns with their deepest hopes.

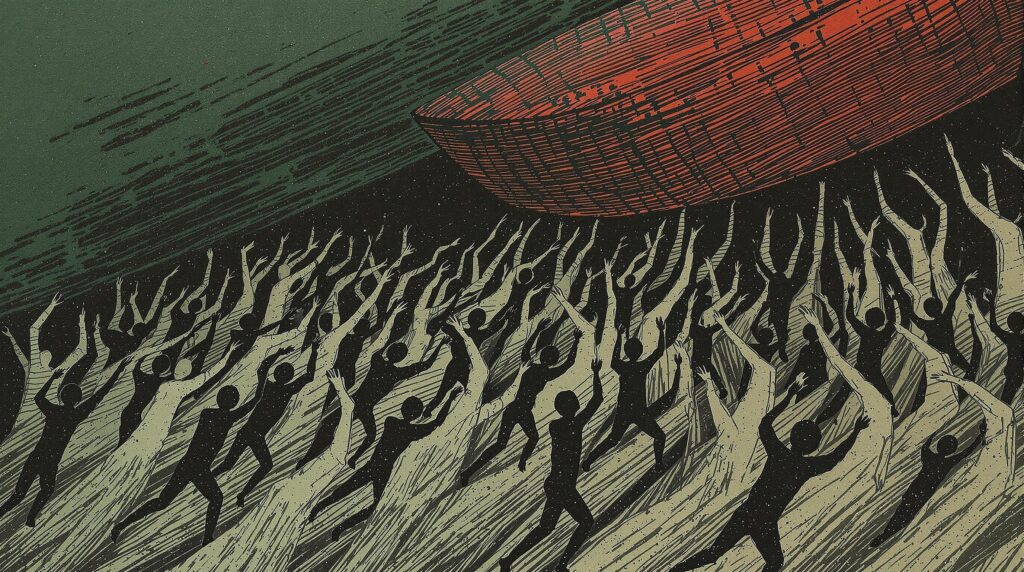

He contrasts the wisest with the unwise masses, likening the people to a river carrying a boat laden with value judgments. In this metaphor, the values of good and evil believed by the people originate from the wisest, who have placed these esteemed guests—value judgments—into the vessel of societal belief. The river of becoming must carry this boat, regardless of the turbulence beneath.

The unwise, of course, the people – they are like the river on which a boat drifts; and in that boat, solemnly and disguised, sit the valuations.

Zarathustra warns that the true danger to the wisest is not the river itself but the very “Will to Power”, described as the inexhaustible, generative life-will. To elucidate his insights, he recounts his observations of living beings. He notes that wherever life is found, so too is obedience; all living things obey something. Those incapable of self-obedience are commanded by others, and commanding is fraught with greater difficulty and risk than obeying. Commanding entails bearing the burden of those who obey and the inherent risks of asserting authority.

Life itself, personified, speaks to Zarathustra, revealing that it is fundamentally about self-overcoming. Life prefers to perish rather than deny this singular will. Wherever there is downfall and decay, life sacrifices itself for the sake of power. This self-overcoming necessitates struggle, becoming, and the pursuit of conflicting purposes, highlighting the intricate pathways the “Will to Power” must navigate.

Zarathustra challenges the concept of a “Will to Existence” or a “Will to Life”, declaring that such wills do not exist because entities already in existence cannot will to exist. Instead, he posits that wherever life is present, so too is the “Will to Power”. He observes that living beings value many things above life itself, and it is through these values that the “Will to Power” expresses itself.

Concluding his discourse, Zarathustra addresses the transient nature of good and evil, asserting that they are not eternal but must continually overcome themselves. Those who are creators in matters of good and evil must first be destroyers, breaking previous values to forge new ones. He emphasizes that the highest good necessitates the presence of the highest evil, underscoring the transformative power of creative destruction.