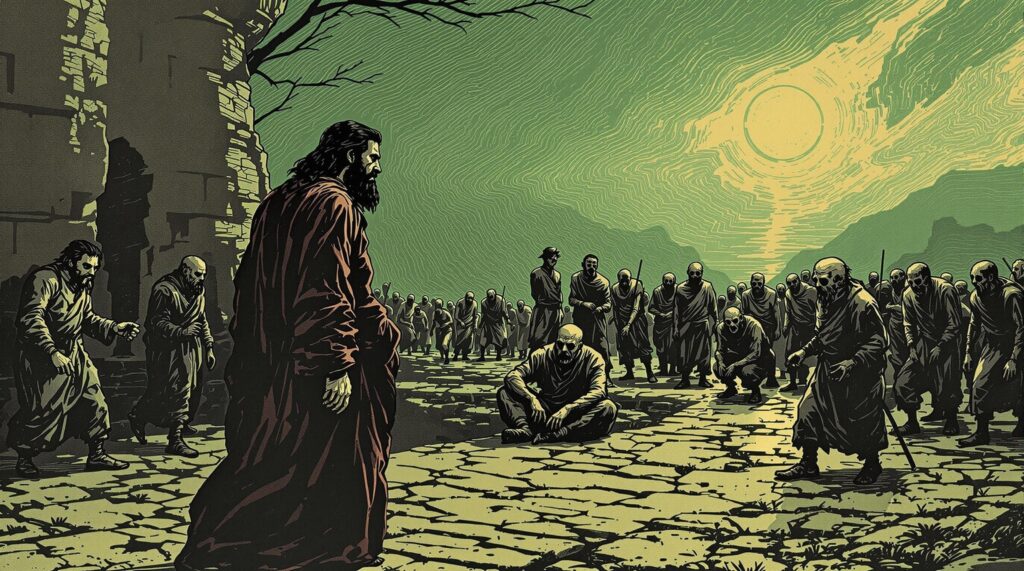

In this chapter, Zarathustra crosses “the great bridge” and is surrounded by cripples and beggars. A hunchback among them addresses him, noting that the people are beginning to believe in his teachings. However, to fully convince them, Zarathustra must also persuade the cripples. The hunchback suggests that performing miracles—such as healing the blind and making the lame walk—would make them believe in him.

As Zarathustra was going across the great bridge one day, the cripples and beggars

surrounded him

Zarathustra responds by questioning the value of such healings. He observes that removing a hunchback’s hump might also remove his spirit, and giving sight to the blind could expose them to harsh realities, leading them to curse their healer. Enabling the lame to walk might allow their vices to spread more rapidly. He reflects on the idea that healing physical ailments does not necessarily lead to true well-being.

He then describes encountering “inverse cripples”—individuals who lack everything except one overly developed feature. For instance, he speaks of a man who is nothing but a giant ear attached to a small, pitiable body. This person is celebrated by the people as a great man or genius, but Zarathustra sees him as an inverse cripple, having too much of one aspect and too little of everything else.

Turning to his disciples with deep discontent, Zarathustra expresses that he feels surrounded by fragments and dismembered limbs of humans, akin to a battlefield strewn with remnants. He is troubled by the absence of whole, complete individuals in both the present and the past. This realization is nearly unbearable for him, and only his vision of the future sustains him. He sees himself as a seer, a willer, a creator, and a bridge to the future, yet also acknowledges himself as a kind of cripple on this bridge.

Zarathustra delves into a contemplation of the human will. He identifies the will as a liberator and bringer of joy but notes that it is still imprisoned by its inability to change the past (“It was”). This helplessness leads to resentment and a desire for revenge against time and existence. The will becomes self-destructive, turning its frustration into harmful actions against all that can suffer.

He criticizes the “spirit of revenge” and the conception of justice, which he considers to be centered on punishment. This worldview, he suggests, is born from the will’s inability to accept the unchangeable past. It leads to the nihilistic thought that because everything passes away, all existence is deserving of destruction. Zarathustra questions whether the will can become its own redeemer by reconciling with time and overcoming any tendency toward vengeance, which must be achieved by willing all that has been into a “thus I willed it”.