In this chapter, Zarathustra contemplates his relationship with humanity and his aspiration towards the Übermensch. The chapter unfolds as an introspective monologue wherein Zarathustra reveals his inner conflict, termed as his “double will”.

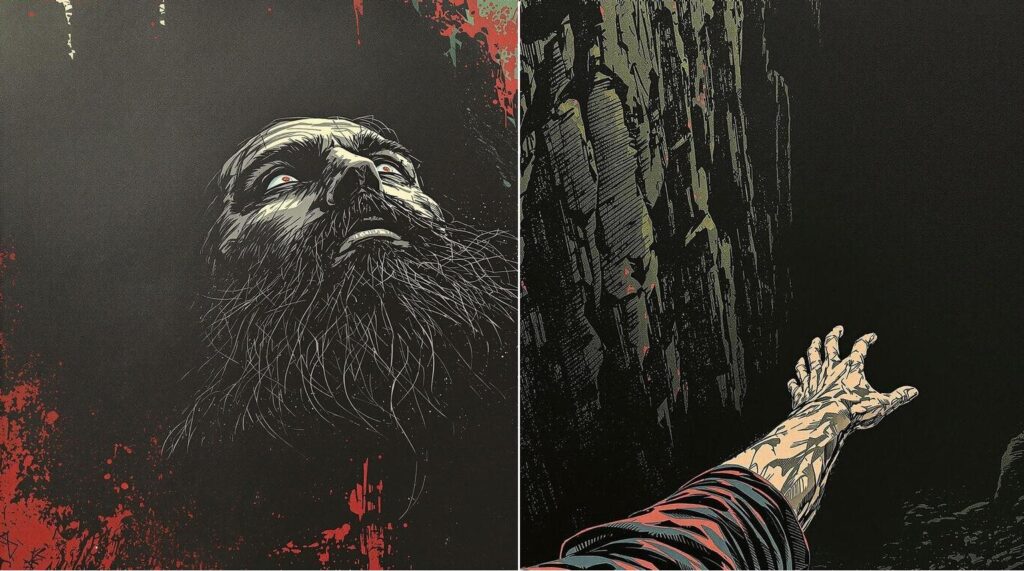

Zarathustra begins by contrasting the fear of heights with the terror of the precipice. He then speaks of his own heart’s “double will”: his gaze is drawn upward towards the Übermensch, while his hand reaches downward, wanting to cling fast to humanity,

Ah, friends, can you also guess my heart’s double will? This, this is my downfall and my danger, that my gaze plunges into the height, and that my hand wants to hold and support itself – to the depths!

Addressing his friends, Zarathustra questions whether they understand this inner turmoil. He confesses that his connection to humanity is both a chain and an anchor, tethering him to the very thing he wishes to transcend. He deliberately lives “blind among humans”, acting as if he does not truly know them, in order to maintain his “faith in that which is firm” and prevent himself from being entirely detached.

Zarathustra explains his first strategy of human cleverness: he allows himself to be deceived to avoid becoming perpetually guarded against deceivers. By doing so, he maintains a connection with humanity. He expresses that being constantly on guard would sever his ties to humans, making them incapable of anchoring him.

His second strategy involves his treatment of the vain and the proud. Zarathustra states that he spares the vain more than the proud, recognizing that wounded vanity is the source of all tragedies. In contrast, wounded pride may give rise to something greater than pride itself. He observes that the vain are excellent actors who desire to be watched, investing all their spirit into this endeavor. Their self-invention and performances provide Zarathustra with relief from melancholy and keep him engaged with humanity. He acknowledges the deep modesty underlying their vanity, as they seek validation and belief in themselves from others. Unaware of their own modesty, they even believe lies told about them when flattered. Zarathustra feels compassion for them, recognizing their inner doubts epitomized by the silent question, “What am I?”

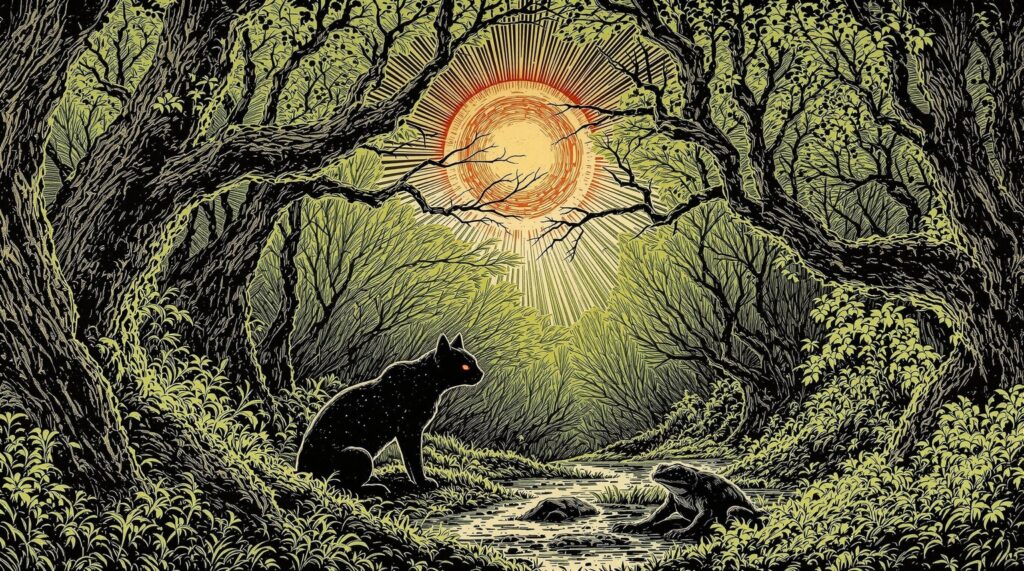

Zarathustra’s third strategy pertains to his perception of the wicked. He refuses to let the sight of evil be tainted by the fearfulness of others. He finds joy in witnessing the “wonders” that a hot sun breeds—tigers, palms, and rattlesnakes—paralleling the wondrous and fierce aspects found among the wicked in humanity. He suggests that just as nature produces formidable creatures, human wickedness can give rise to remarkable phenomena. Zarathustra notes that what is currently deemed the greatest evil is insignificant compared to what may yet emerge. He anticipates the arrival of greater “dragons” in the future, implying that the evolution of humanity will bring forth more profound challenges and evils that are necessary for the Übermensch to overcome.

For, that the Übermensch shall not lack his dragon, the over-dragon that is worthy of him: for that must much hot sun yet shine upon damp primeval forest! Out of your wild cats must tigers have developed, and out of your poison-toads, crocodiles: for the good hunter shall have a good hunt!

He reflects on the “good and just”, finding amusement in their fear of what has traditionally been labeled as the “devil”. Zarathustra suggests that their souls are so disconnected from greatness that the Übermensch’s goodness would seem terrifying to them. He also addresses the “wise and knowledgeable”, predicting that they would flee from the burning brightness of the wisdom in which the Übermensch thrives. The “highest men” he has encountered provoke his doubt and secret laughter; he surmises they would label his Übermensch as the devil.

Weary of these “highest and best” individuals, Zarathustra feels compelled to move beyond them. He experiences a shudder upon seeing them stripped of their pretenses, prompting him to metaphorically grow wings and ascend into distant futures and sunnier realms than any artist has imagined. These “sunnier souths” symbolize uncharted territories of human potential, where even gods might be ashamed of their garments.

In Zarathustra’s final human cleverness, he resolves to disguise himself among people, allowing them to continue as the “good and just”. By doing so, he seeks to misrecognize both them and himself. This act allows him to remain connected to humanity while simultaneously pursuing his vision of the Übermensch without being hindered by the limitations and judgments of those around him.