In this chapter, Zarathustra reflects on his previous belief in a world beyond the human realm and narrates his journey toward embracing the physical world.

Zarathustra begins by admitting that he once shared the illusions of the “Hinterweltlern”, those who believe in an afterworld or a transcendent realm beyond humanity. He perceived the world as the creation of a suffering and tormented deity—a dream or poetic vision of a dissatisfied god. Concepts such as good and evil, pleasure and pain, self and other appeared to him as insubstantial as colorful smoke before the eyes of a divine creator seeking to turn away from himself.

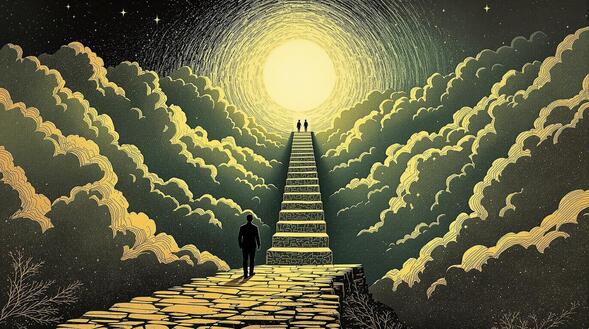

Thus I, too, once cast my delusion beyond the human, like all believers in a world behind.

He recounts how this creator, desiring to avert his gaze from his own suffering, fashioned the world as a means of self-forgetfulness—a “drunken joy” for the one in pain. Zarathustra realizes that his own belief in such a god was a product of human madness, a mere fragment of humanity and a projection of his own self. This phantom arose from his own ashes and flames, not from any otherworldly source.

Through self-overcoming, Zarathustra carries his own ashes up the mountain and kindles a brighter flame within himself. As he does so, the phantom of the suffering god dissipates. Now recovered, he finds it painful and demeaning to believe in such specters. He addresses the “Hinterweltlern”, asserting that their creation of afterworlds stems from suffering and incapacity—a weariness that longs for a final leap into oblivion.

Zarathustra critiques this desire to escape the body and the earth, suggesting that it was the despairing body itself that concocted notions of gods and afterworlds. The body, unable to will or endure, grasped at the idea of a transcendent realm. He urges his listeners to heed the voice of the healthy body, which speaks honestly and purely about the meaning of the earth.

Zarathustra acknowledges that poets and those yearning for gods have often despised the body and the earth, inventing heavenly realms and redemption through suffering. Yet, even these notions are derived from the body and the earth they seek to escape. By rejecting the concept of an afterworld, he calls for a revaluation of values, placing humanity and the tangible world at the center of meaning.