In this chapter, Zarathustra observes the moon rising and contemplates its appearance. He remarks that the moon seems so broad and pregnant on the horizon that he imagined it might give birth to the sun. However, he accuses the moon of deceit in its apparent pregnancy and expresses skepticism towards it

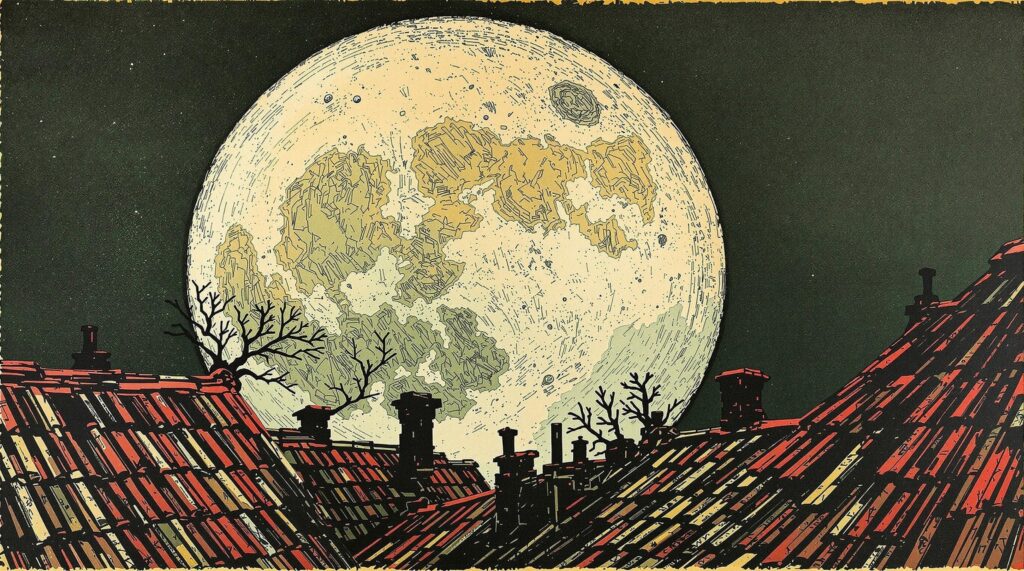

Zarathustra describes the moon as a timid night-roamer with a bad conscience, comparing it to a jealous monk lusting after the earth and the joys of lovers. He expresses disdain for the moon, likening it to a cat stealthily moving over rooftops and disliking its silent, cautious footsteps. He criticizes those who, like the moon, sneak around half-closed windows, finding such behavior distasteful.

When the moon rose yesterday, I thought it wanted to give birth to a sun: so broad and pregnant did it lie on the horizon.

Addressing the “sensitive hypocrites” and the “immaculate perceivers”, Zarathustra calls them lustful, accusing them of loving the earth and earthly things with shame and bad conscience. He suggests that while they have been persuaded intellectually to despise the earthly, their innermost desires—their “entrails”—remain potent. This internal conflict leads their spirit to take secretive and deceitful paths, ashamed of its servitude to their desires.

He mocks their aspiration to observe life without desire, likening it to a cold, ash-gray state with “drunken moon eyes”—a passive observation devoid of will and longing. They wish to love the earth as the moon does, touching its beauty only with their eyes, seeking an “immaculate knowledge” that desires nothing from things except to lie before them like a mirror with a hundred eyes. Zarathustra finds fault in this detached approach, suggesting it lacks innocence because it denies the natural desire and will to create.

Zarathustra contrasts their perspective with the concept of innocence found where there is a will to procreation and creation—where one wishes to go beyond oneself. He emphasizes that beauty exists where there is an irresistible will, a desire to love and to perish so that an image does not remain merely an image. The notions of loving and perishing have been intertwined eternally, and the will to love entails a willingness to face death. He challenges the “cowards” who avoid this truth.

He criticizes the so-called “contemplative” individuals whose emasculated squinting they label as contemplation, and who name what they can touch with fearful eyes as beautiful, thus degrading noble terms. Zarathustra declares that their curse is their barrenness—they will never give birth, even if they appear broad and pregnant on the horizon like the moon. He accuses them of using grand words without genuine feeling, suggesting that their noble phrases are deceitful.

He reveals that they have disguised their true selves with a god’s mask to deceive even themselves, hiding a monstrous worm beneath divine façades. Zarathustra admits he was once fooled by their godly appearances, not recognizing the coiled serpent within. However, upon closer proximity, he perceived the deception, and now the dawn arrives—the affair of the moon has ended.

As the glowing dawn approaches, Zarathustra notes the sun’s love for the earth, characterized by eagerness and fervor. The sun wishes to imbibe the sea’s depths, and the sea yearns to be kissed and drawn upwards, transforming into air and light. Aligning himself with the sun, Zarathustra declares his love for life and all profound depths. For him, knowledge means that all that is deep strives to rise to his elevation.