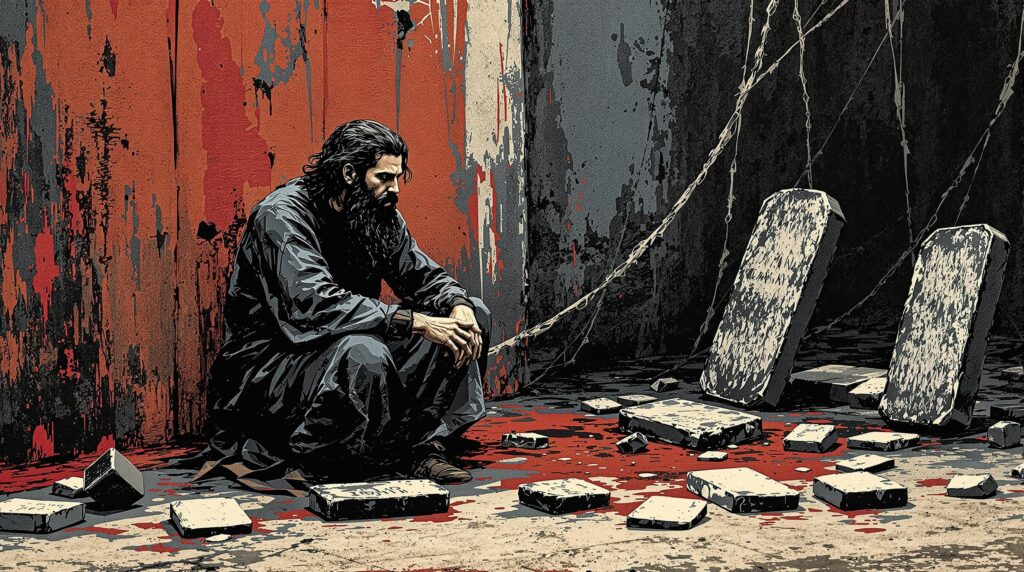

In the chapter On Old and New Tablets, the longest chapter in the book, Zarathustra reflects on his teachings and his journey thus far, and prepares to impart new wisdom to humanity. He sits surrounded by old, broken tablets and new, half-written ones, symbolizing the destruction of outdated values and the anticipation of new ones. He awaits his “hour”, the moment of his descent to mankind, signified by the coming of a “laughing lion with a flock of doves”.

Here I sit and wait, old broken tablets around me and also new half-written tablets. When will my hour come?

He recalls his earlier encounters with humanity, finding people complacent, resting on the “old conceit” that they knew what was good and evil. Zarathustra disrupted this by declaring that no one truly knows good and evil except the creator—the one who sets new goals and gives the earth meaning. He encouraged the overthrow of old moral authorities, urging laughter at the solemnity of virtue teachers, saints, poets, and world redeemers who, like “black scarecrows”, warned from the tree of life.

Zarathustra describes his own wisdom as born on the mountains, wild and yearning, often carrying him into ecstatic visions of future times and places where gods dance unashamed. He expresses a tension between his prophetic insights and his role as a poet, feeling shame that he must still speak in metaphors and parables.

He recounts how he discovered the concept of the Übermensch on his path. To him, humans are a bridge, not an end, and he spoke of the “great noontide”, symbolizing a peak of human possibility. He taught the importance of unifying the fragmented parts of humanity, transforming chance and past events into a creation of will, thereby redeeming the past.

Awaiting his final descent to humanity, Zarathustra wishes to bestow his “richest gift” before his departure. He draws a parallel to the sun, which, in setting, pours its abundance into the sea, enriching even the poorest fishermen.

He introduces new tablets but seeks companions to help carry them into the hearts of people. He challenges his audience to take rights rather than wait for them to be given, and to command themselves.

Zarathustra criticizes those who are “good and just”, suggesting they hinder humanity’s progress by clinging to outdated morals. He asserts that the creation of new values requires a confluence of qualities—boldness, skepticism, and even a capacity for cruelty toward one’s own beliefs. He calls for the breaking of old tablets to make way for new ones.

He addresses the transitory nature of values and the danger posed by those who, rooted in the past, resist change. Zarathustra foresees new peoples and cultures emerging from societal upheavals, comparing these to new springs bursting forth after an earthquake. He speaks of the need for a new nobility that looks forward, not backward, and compels those to whom he directs his teachings to love the land of their children rather than the land of their ancestors.

In his concluding thoughts, Zarathustra urges his followers to become creators of their own destiny, to be “hard” in the sense of being resolute and unwavering in the face of challenges. He prepares himself for a great victory, invoking his will as the force that transforms necessity into his own necessity.