In this chapter, Zarathustra departs from the town called “The Colourful Cow”. As he leaves, many who call themselves his disciples accompany him. Upon reaching a crossroads, Zarathustra informs them that he wishes to continue alone. His disciples bid him farewell by presenting a staff with a golden handle, around which a serpent coils about the sun. Zarathustra accepts the staff with joy and uses it for support; he then addresses his disciples.

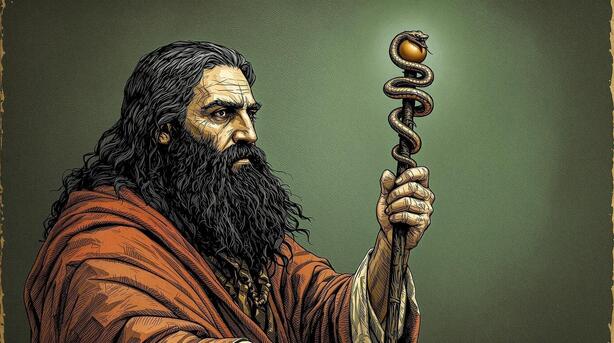

But his disciples gave him, in farewell, a staff whose golden handle bore a snake coiled around the sun.

Zarathustra reflects on why gold has attained the highest value. He suggests that gold is esteemed because it is rare, useless, radiant, and gentle in its glow—it perpetually gives of itself. Drawing a parallel, he asserts that gold became valuable as an image of the highest virtue. This highest virtue is uncommon, unprofitable, luminous, and gentle in its radiance—a virtue that bestows and gives generously.

He perceives that his disciples aspire, as he does, for this bestowing virtue. This bestowing love, he notes, must become a kind of noble robbery of all values, yet he calls this self-interest “holy and sacred”.

Together with his disciples he questions what is evil and the worst evil, proposing that it is degeneration, and that wherever the giving soul is absent, one suspects. degeneration.

Zarathustra describes the body as progressing through history—a becoming and a contending—and the spirit as its herald and echo. All names of good and evil are mere symbols that hint but do not fully express; seeking definitive knowledge from them is folly. He urges his disciples, in a musical form of speech, to heed moments when their spirit speaks in symbols, for therein lies the origin of their virtue.

Thus the body goes through history, a becoming and a fighting.

He proclaims that their virtue is a new concept of good and evil—a deep murmur and the voice of a new source. This new virtue is power, a commanding thought surrounded by a wise soul; it is a golden sun encircled by the serpent of knowledge.

After a pause, Zarathustra continues, his tone altered. He implores his disciples to remain faithful to the earth through the power of their virtue. Their bestowing love and knowledge should serve the meaning of the earth.

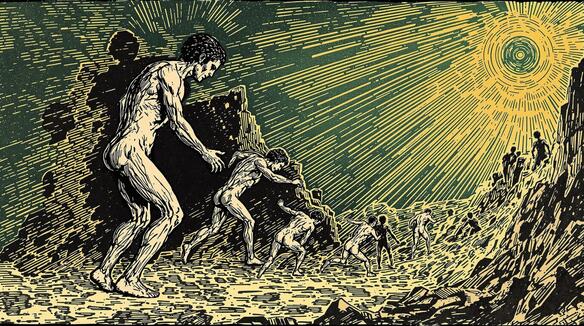

He urges them to guide misguided virtue back to earth, back to the body and life, so that it may imbue the earth with human meaning. He observes that both spirit and virtue have erred and strayed throughout history—humanity has been a trial and a misdirection, with much ignorance and error becoming embodied within it. The madness and reason of millennia manifest within it, making inheritance perilous. Humanity still contends with the giant called Chance, under the sway of unreason.

He advises them, “Physician, heal thyself”, so they may aid others by exemplifying self-healing. He speaks of untraveled paths and undiscovered human potentials—humanity and the human earth remain unexhausted and unexplored. He urges the solitary and those who withdraw to remain vigilant; winds from the future bring subtle messages, and to attentive ears, good tidings arrive.

Zarathustra foretells that those who are solitary today will one day form a people—a chosen people—from whom the Übermensch will emerge. He envisions the earth becoming a place of healing, imbued with new fragrance and hope.

After another pause, during which Zarathustra weighs the staff in his hand, he speaks again, his voice changed. He announces that he now will go alone and that his disciples too must depart and be alone; this is his will. He advises them to leave him and to guard themselves against Zarathustra, even suggesting they should be ashamed of him, for perhaps he has deceived them.

Zarathustra promises that he will seek them again with different eyes and love them anew. He foresees that they will become his friends and children of a singular hope; then he will return to celebrate the “great noon” with them. This “great noon” is the moment when humanity stands midway between beast and Übermensch, celebrating the journey toward the evening as its highest hope—the path to a new morning.