In this chapter, Zarathustra reflects on the nature of criminality, justice, and morality through the examination of a single case: a criminal who has committed murder.

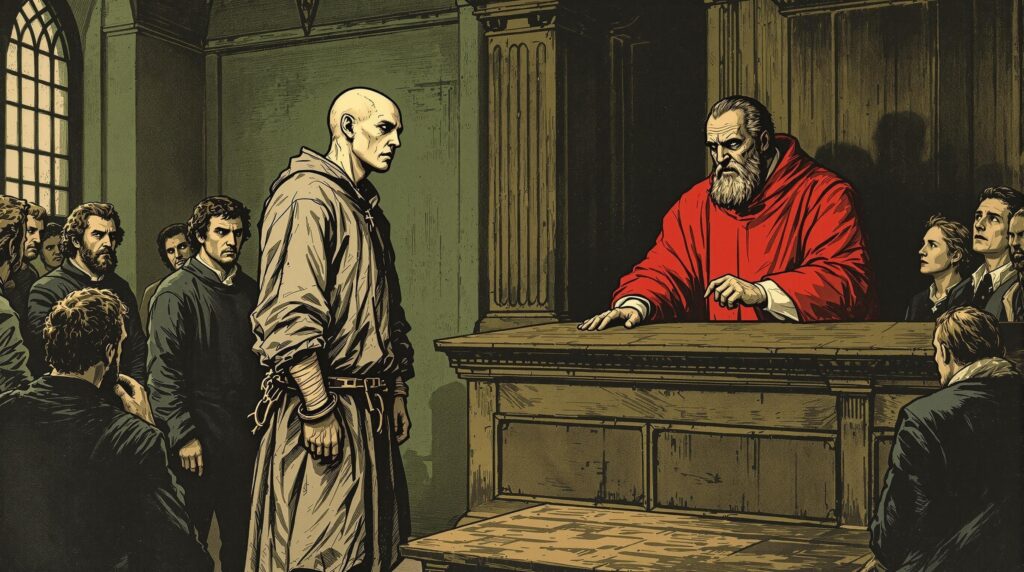

The criminal stands before judges and executioners as a consequence of his heinous act. His pallor suggests inner turmoil, guilt, or a profound existential crisis. Zarathustra delves into the psyche of this individual, asserting that the criminal’s deed was not motivated by conventional reasons such as theft or revenge. Instead, it was an expression of a deeper, irrational desire—an insatiable thirst for the “happiness of the knife,” symbolizing a primal yearning for violence or a release from inner suffering.

Behold this poor body! What it suffered and desired, this poor soul interpreted for itself

Zarathustra addresses the judges (“Richter”) and sacrificers (“Opferer”), critiquing their approach to justice. He urges them not to execute the criminal out of vengeance, and emphasizes that their act of killing should be justified by compassion and a love for the Übermensch.

He advises the judges to reevaluate the language they use in judgment. Instead of labeling individuals as “evildoers”, “scoundrels”, or “sinners”, they should consider terms like “enemy”, “ill person”, or “fool”. This shift in terminology reflects a more empathetic understanding of the criminal’s condition, recognizing the complexity of human behavior beyond moral absolutes.

Zarathustra also confronts the hypocrisy of the “red judge”, suggesting that if the judge were to confess all his own thoughts and desires, society would reject him as well. This highlights the flawed nature of moral judgment.

The narrative explores the distinction between thought, action, and the image of the action. The pale criminal was equal to his deed when committing it, but he could not endure the image of it afterward. This inability leads to madness (“Wahnsinn”), as the exception (the act of murder) becomes his essence. Zarathustra describes a “madness after the deed,” where the criminal’s weakened reason attempts to rationalize the irrational impulse by fabricating motives like robbery or revenge.

Zarathustra laments that the judges fail to understand the deeper “madness before the deed,” indicating a lack of insight into the criminal’s psyche. He suggests that the criminal is like a “bundle of diseases” reaching out into the world, or a “knot of wild serpents” seeking prey—metaphors for internal chaos manifesting externally.