In this chapter, Zarathustra engages in a dialogue with one of his disciples. The conversation centers on the nature of poets and poetry.

Zarathustra begins by reflecting on his deeper understanding of the body, stating that the spirit has become to him merely “quasi-spirit”, and all that is “imperishable” is merely a metaphor. The disciple recalls Zarathustra’s previous assertion that poets lie too much and inquires about the reason behind this claim.

Zarathustra responds evasively, indicating that he is not one to be questioned about his reasons. He remarks that his experiences and the foundations of his opinions are not recent and that keeping track of the reasons would require an exhaustive memory. He notes that even retaining his own opinions is burdensome, as some ideas escape him like birds. Occasionally, unfamiliar thoughts enter his mind unexpectedly, trembling under his scrutiny.

Acknowledging that he himself is a poet, Zarathustra questions whether his statement about poets lying was truthful. The disciple professes his belief in Zarathustra, but Zarathustra dismisses this faith as insufficient, especially belief in himself.

He then critiques poets collectively, asserting that they lie too much due to their limited knowledge and poor learning. Poets, according to Zarathustra, adulterate their creations—comparable to tainting wine—producing toxic mixtures in their metaphorical cellars.

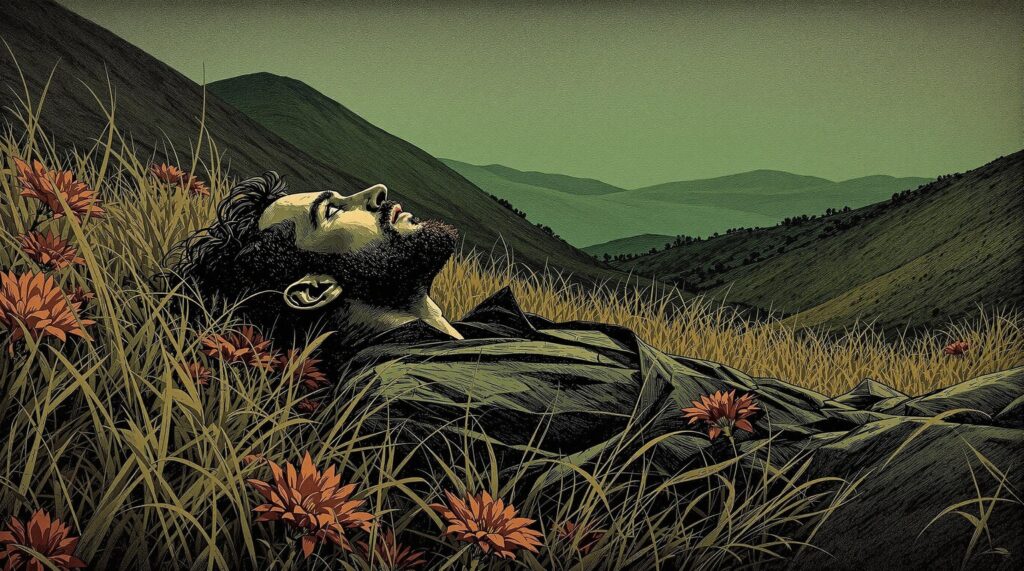

But this is what all poets believe: that whoever lies in the grass or on lonely hillsides with ears perked up learns something of the things that are between heaven and earth. And if tender emotions come to them, the poets always think that nature herself is in love with them.

Zarathustra observes that poets believe in a special, concealed access to knowledge that eludes those who actively learn. They hold that by attuning themselves to nature—lying in grass or on solitary slopes—they can perceive truths between heaven and earth. When moved by tender emotions, they imagine that nature is in love with them, whispering secrets and flattery, which they boast about to others.

He laments that many things between heaven and earth have been only dreamt of by poets, especially concerning what lies above the heavens. Zarathustra declares that all gods are metaphors and illusions crafted by poets. He criticizes poets for ascending to the realm of clouds, placing their fanciful creations—gods and over-men—upon them, which are light enough to sit on such insubstantial seats.

Expressing fatigue, Zarathustra admits weariness of the insufficient creations that are deemed significant events, particularly those of poets. His disciple becomes angry but remains silent. Zarathustra also falls silent, his gaze turning inward as if looking into distant realms. After a sigh, he speaks of being of both today and former times, yet possessing something within that belongs to tomorrow, the day after, and once upon a time.

He expresses his exhaustion with both old and new poets, considering them superficial like shallow seas. They have not contemplated deeply enough, and thus their emotions have not delved to profound depths. Their deepest reflections have been mere moments of pleasure and boredom. He regards their musical expressions as insubstantial, lacking true passion.

Zarathustra accuses the poets of impurity, suggesting they muddy their waters to appear deep. They present themselves as mediators and reconcilers but remain compromised and unclean in his view. Even when he sought valuable insights from their works, he retrieved only remnants of outdated beliefs.

Concluding his discourse, Zarathustra foresees a transformation among poets. He has observed poets becoming weary of themselves, turning their scrutiny inward. From them, he has seen the emergence of “penitents of the spirit”, indicating a shift towards a movement towards a more authentic and profound expression.