Thus Spoke Zarathustra begins with a prologue that is rich in symbolism and philosophical underpinnings, setting the foundation for the themes explored throughout the work. The prologue introduces the central character Zarathustra, and outlines his journey from isolation to engagement with humanity, as he seeks to impart his vision of the Übermensch.

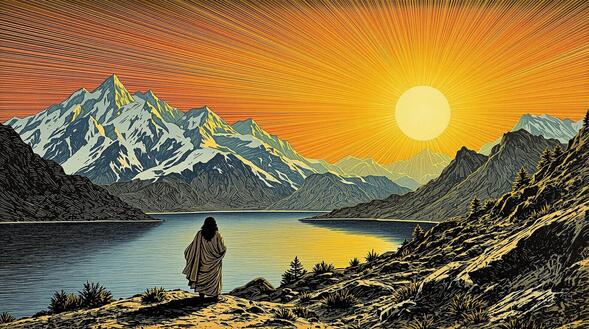

“Great star! What would your happiness be if it were not for those for whom you shine!

At the age of thirty, Zarathustra departs from his homeland and retreats to the mountains, staying there for ten years. This period of seclusion allows him to accumulate wisdom and insight. But an inner transformation compels him to return to humanity again in order to to illuminate others.

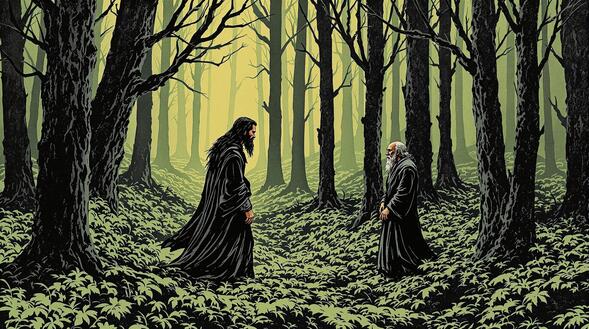

As he descends from the mountains, Zarathustra encounters an old saint in the forest. The saint recognizes Zarathustra but notes his transformation. He remarks that Zarathustra once ascended the mountains bearing ashes, and now he appears to descend with fire. The saint questions whether Zarathustra fears the consequences of bringing his fire to the valleys.

They are suspicious of solitaries, and do not believe that we come to bestow.

The saint himself embodies traditional religious devotion. He reveals that he once loved humanity deeply but retreated to the forest because his love became overwhelming. Now, he loves God instead of people, considering mankind too imperfect and his love for them potentially fatal to himself. Zarathustra declares that he loves humanity and intends to bring them a gift—the wisdom he has cultivated during his solitude. The saint advises Zarathustra not to give anything to people but rather to take something from them or share in their burdens. He warns that people are mistrustful of hermits bearing gifts.

After parting ways with the saint, Zarathustra reflects on the encounter. He is surprised to discover that the saint is unaware of the profound shift in belief—that “God is dead”. This realization emphasizes the disconnect between old religious values and the new philosophical paradigm Zarathustra represents.

Continuing his journey, Zarathustra arrives at a town situated near the forests, where a crowd has gathered in the marketplace to witness a tightrope walker. Seizing the opportunity, he addresses the people there, proclaiming his teaching of the Übermensch. He asserts that the human being is something that must be overcome. Drawing on the progression of life-forms, he notes that all creatures have evolved beyond themselves, and asks whether humanity now wishes to halt this progression or even regress. He compares humans to apes, suggesting that just as apes are a source of laughter or shame to humans, so should humans be to the Übermensch.

Zarathustra presents a metaphor of the human as a rope tied between animal and Übermensch—a bridge over an abyss. This metaphor illustrates the precarious and transitional nature of human existence. He proclaims that what is great in humans is not that they are an end but that they are a means, a bridge, and a transition.

The human is a rope, tied between beast and Übermensch – a rope over an abyss.

However, the people in the marketplace misunderstand Zarathustra’s message. They are more interested in the spectacle of the tightrope walker and mock Zarathustra, failing to grasp the profundity of his words. They demand to see the tightrope walker perform, revealing their preference for entertainment over philosophical discourse.

Undeterred, Zarathustra continues his address, warning of the coming of the “final human”, a being who represents the antithesis of the Übermensch. The final human is characterized by complacency, mediocrity, and a lack of ambition. It seeks only comfort and trivial pleasures, avoiding any risk or challenge that might lead to personal growth or the advancement of humanity.

Amidst his speech, the tightrope walker begins his performance, serving as a living metaphor for Zarathustra’s teachings. As he traverses the rope, a jester—a buffoonish and disruptive figure—emerges and taunts him. The jester’s mocking and threatening behavior causes the tightrope walker to lose his composure, leading to a fatal fall.

You have made danger your calling: in that there is nothing to despise

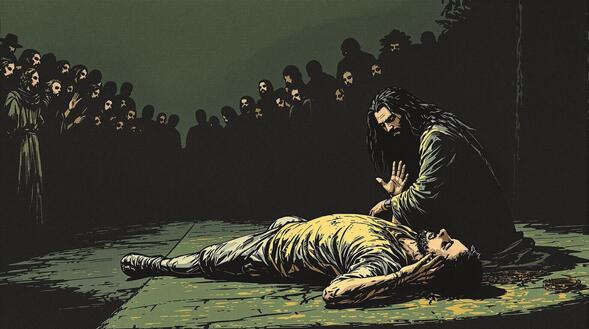

Zarathustra approaches the fallen tightrope walker, who is gravely injured but not yet dead. The dying man fears that the devil will take him to hell. Zarathustra reassures him, asserting that there is no devil and no hell, and that his soul will soon be as dead as his body. He tells the man to fear nothing more. The tightrope walker responds by acknowledging that if this is true, he has lost nothing in losing his life, as he was merely like an animal trained to perform through blows and meager rewards. Touched by his plight, Zarathustra promises to bury him with his own hands, honoring the man’s embrace of danger as his profession.

As evening falls and the marketplace empties, Zarathustra remains beside the dead man, deep in thought. He reflects on the absurdity and meaninglessness that can pervade human existence, noting that it takes only a trivial figure—a jester—to bring about tragedy. Recognizing that his teachings have not resonated with people and that he is perceived as either a fool or associated with the dead, he resolves to carry the body away.

While carrying the corpse out of the city, Zarathustra encounters the jester who had caused the tightrope walker’s fall. The jester warns him to leave the town, as many people there hate him—the virtuous label him an enemy and scorner, and the faithful see him as a danger to the multitude. The jester suggests that Zarathustra was fortunate to be laughed at, as it spared him from greater harm. He implies that if Zarathustra does not leave, he may become the next victim.

As he passes through the city gates, Zarathustra meets the gravediggers, who mock him for carrying the “dead dog”. They jest that Zarathustra has become a grave-digger himself and taunt him with the possibility that the devil might steal both the corpse and him. Despite their ridicule, Zarathustra remains silent.

Continuing his journey, Zarathustra becomes hungry and stops at a solitary house where an old man provides him with food and drink. The old man notes that the area is inhospitable for the hungry, offering an equal share of bread and wine to both men, indifferent to the fact that one of the men is dead.

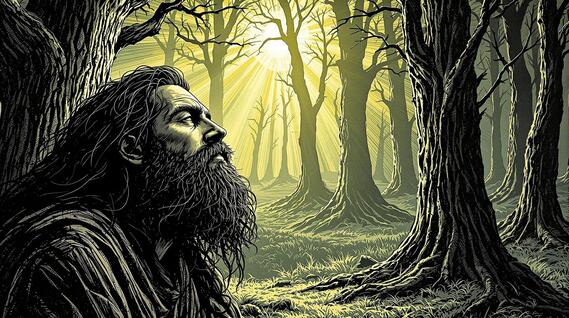

After resting, Zarathustra enters a deep forest, where he lays the corpse in a hollow tree to protect it from wolves and lies down to sleep. When he awakens, he experiences a moment of profound clarity. He realizes that he must seek companions who are willing to embrace and further his ideas, rather than attempting to reach the masses who are not prepared to understand him. He concludes that he is not destined to be a shepherd leading a herd or a gravedigger focusing on the dead. Instead, he seeks fellow creators—individuals who will join him in cultivating new values and harvesting the ripe fruits of possibilities.

A light has dawned on me: I need companions, and living ones – not dead companions and corpses that I carry with me wherever I will.

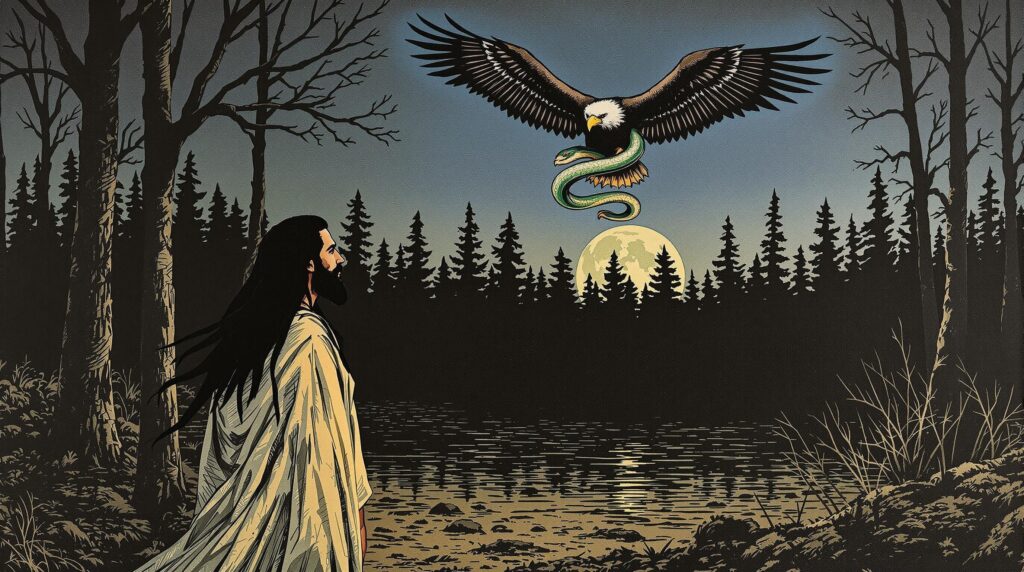

As he sets forth with this renewed purpose, Zarathustra looks upward and sees an eagle soaring in wide circles overhead, with a serpent entwined around its neck—not as prey, but as a companion. Recognizing them as his animals—the proudest and the wisest—Zarathustra interprets their presence as a symbolic affirmation of his quest. The eagle represents nobility, strength, and the ability to soar to great heights, while the serpent symbolizes wisdom, cunning, and the knowledge of the depths. Together, they embody the dual aspects of his own nature and the qualities required for his mission.

The proudest animal under the sun and the cleverest animal under the sun – they have come out on reconnaissance.

The prologue culminates with the phrase “Thus began Zarathustra’s down-going”, which conveys a sense of both literal descent and metaphorical self-sacrifice. The prologue functions as a microcosm of the broader work, introducing key philosophical concepts and setting the stage for Zarathustra’s continued journey.