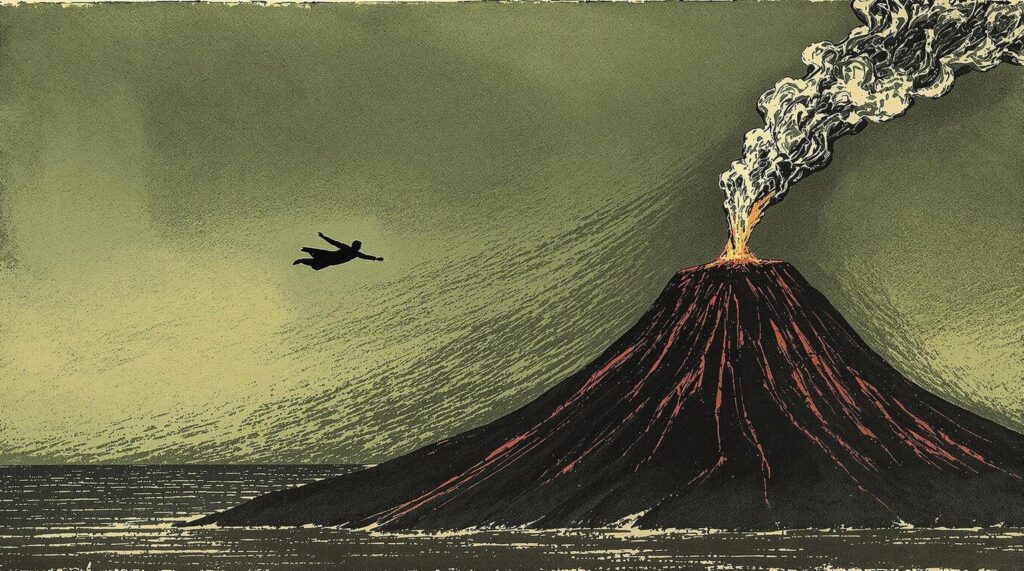

The narrative of this chapter begins with a depiction of an island in the sea near Zarathustra’s “Blessed Isles”. This island is notable for its perpetually smoking volcano. The local populace believe that the island is placed like a rock before the gate to the underworld. They assert that a narrow path through the volcano leads downward to this gate.

During Zarathustra’s stay on the Blessed Isles, a ship anchors at the island of the smoking mountain. The crew disembarks to hunt rabbits. Around midday, as the captain and his men regroup, they witness a remarkable sight: a man flying through the air toward them. A voice clearly proclaims, “It is time! It is the highest time!” As the figure swiftly passes by, heading toward the volcano, the sailors recognize him as Zarathustra. All except the captain had seen him before and felt a mixture of love and awe for him.

Around the hour of midday, however, when the captain and his men were together again, they suddenly saw a man coming towards them through the air, and a voice said distinctly: ‘It is time! It is the highest time!’

Simultaneously, rumors circulate that Zarathustra has vanished. But on the fifth day, Zarathustra reappears among his followers, eliciting great joy. He proceeds to recount his encounter with the “Fire-Hound”. He begins by likening the earth to a creature with a diseased skin, naming “the human” as one such affliction and the “Fire-Hound” as another. He notes that people have fabricated many tales about the Fire-Hound, perpetuating misunderstandings.

Seeking the truth, Zarathustra crosses the sea and confronts the Fire-Hound, demanding it reveal the depth of its origin. He observes that the Fire-Hound’s expressions are tainted by the sea’s influence—its “over-salted eloquence” suggests it draws from surface-level sources rather than profound depths. Zarathustra accuses the Fire-Hound of being a mere “ventriloquist of the earth”, with rhetoric that is salty, deceitful, and shallow. He criticizes the creature’s tendency to bellow and obscure matters with smoke and ash, skills that serve to agitate rather than enlighten.

Zarathustra expresses skepticism toward the loud proclamations of “freedom” made by entities like the Fire-Hound. He remarks that he has lost faith in so-called “great events” that are accompanied by much noise and smoke. Instead, he posits that the most significant events occur in the quietest moments, driven by those who invent new values rather than new noises.

He admonishes those who overthrow statues, deeming it foolish to destroy symbols out of contempt. Zarathustra suggests that such acts only rejuvenate the overthrown entities, allowing them to rise with renewed beauty and even divine features. He advises kings, churches, and all that is aging and morally weak to allow themselves to be overthrown, as this can lead to a revival of virtue and life.

The Fire-Hound interrupts Zarathustra, asking, “Church? What is that?” Zarathustra explains that a church is a form of state—the most deceitful kind. He draws a parallel between the Fire-Hound and the state, both hypocritical and inclined to use smoke and noise to create the illusion of deep significance. The state desires to be the most important entity on earth, a claim that people often accept without question.

This comparison enrages the Fire-Hound, who reacts with jealousy and produces an overwhelming amount of smoke and horrific sounds. Once it calms down, Zarathustra speaks of another Fire-Hound that genuinely emanates from the heart of the earth. This creature breathes gold and laughter, indifferent to ashes, smoke, and internal turmoil. Its joy and precious exhalations come from the earth’s golden heart. This depiction contrasts sharply with the first Fire-Hound’s destructive nature.

Ashamed by this revelation, the Fire-Hound retreats into its cave, acknowledging its lesser stature. Zarathustra concludes his account of the encounter, highlighting the superficiality of loud and aggressive forces compared to the quiet depth of true value creation.

Meanwhile, his disciples are eager to relay the sailors’ tale of the flying man and their other experiences. Zarathustra, puzzled by the sailors’ sighting, wonders if he is perceived as a ghost. He muses that it may have been his shadow, referencing “The Wanderer and His Shadow”. Zarathustra considers disciplining his shadow to prevent it from tarnishing his reputation.

He reflects on the mysterious proclamation heard by the sailors: “It is time! It is the highest time!” Zarathustra is left contemplating the significance of this message, pondering for what purpose it is the highest time.